Twenty-two years before he bet his company on bitcoin, MicroStrategy CEO Michael Saylor sat down for a long interview with Forbes during which he invoked Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Churchill, Caesar and Lincoln. At that point, in 1998, the company was a Wall Street darling, thanks to its dot-com-era software suite. MicroStrategy was doing just $100 million in sales, but Saylor envisioned a day when its technology would be used by “everybody on the planet.” He was 33 and couldn’t see the coming March 2000 crash or that MicroStrategy stock would languish for two decades.

From Forbes, September 7, 1998:

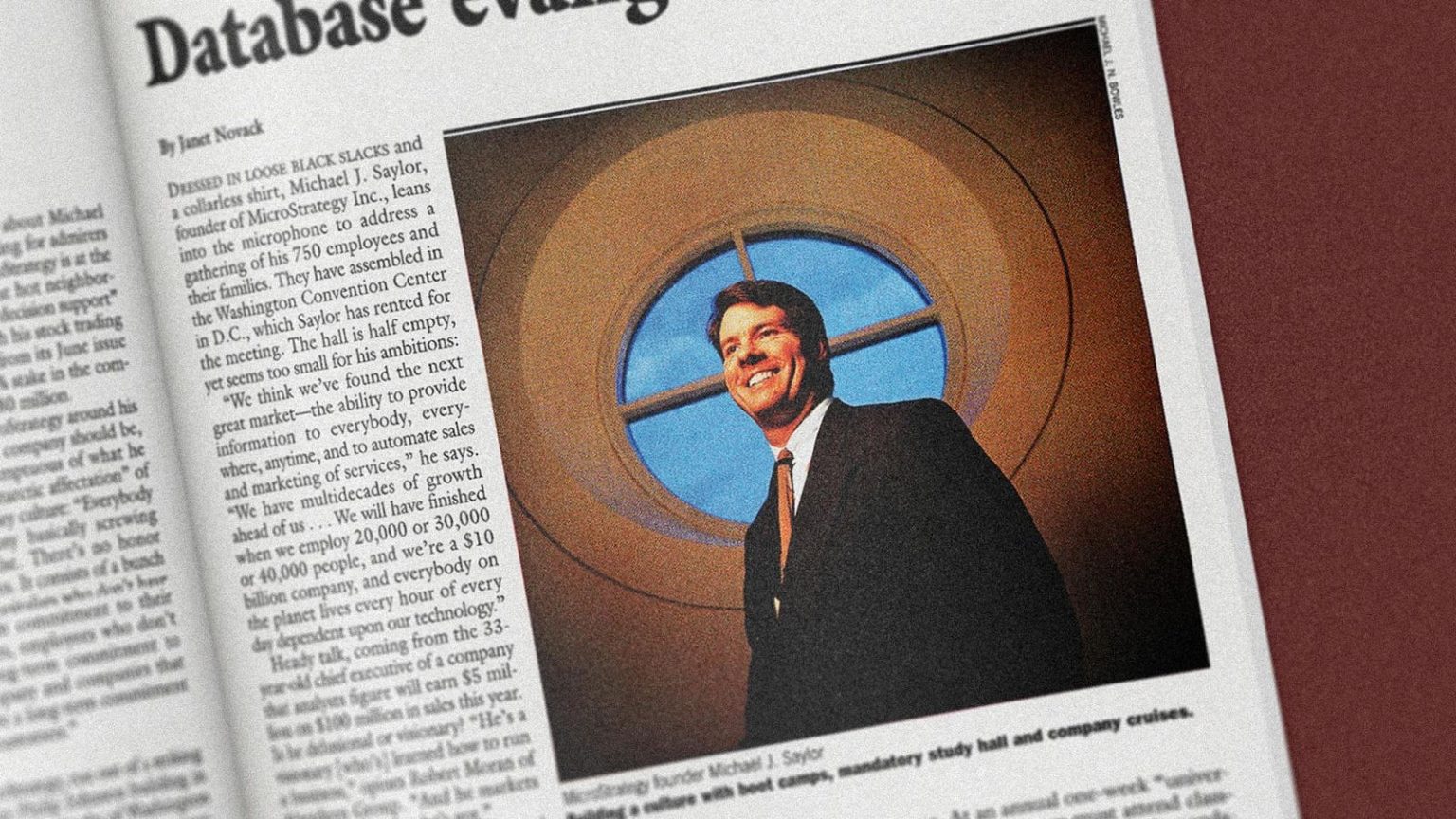

Database Evangelist

Either MicroStrategy’s Michael Saylor is a visionary, or he’s a delusional egomaniac. Either way, big corporate customers are lining up to buy his software.

Dressed in loose black slacks and a collarless shirt, Michael J. Saylor, founder of MicroStrategy Inc., leans into the microphone to address a gathering of his 750 employees and their families. They have assembled in the Washington Convention Center in D.C., which Saylor has rented for the meeting. The hall is half empty, yet seems too small for his ambitions:

“We think we’ve found the next great market — the ability to provide information to everybody, everywhere, anytime, and to automate sales and marketing of services,” he says. “We have multidecades of growth ahead of us . . . We will have finished when we employ 20,000 or 30,000 or 40,000 people, and we’re a $ 10 billion company, and everybody on the planet lives every hour of every day dependent upon our technology.”

Heady talk, coming from the 33-year-old chief executive of a company that analysts figure will earn $ 5 million on $ 100 million in sales this year. Is he delusional or visionary? “He’s a visionary [who’s] learned how to run a business,” opines Robert Moran of Aberdeen Group. “And he markets the hell out of what he’s got.”

Say what you will about Michael Saylor, he is not lacking for admirers on Wall Street. MicroStrategy is at the intersection of some hot neighborhoods — the Web, “decision support” and databases. With his stock trading at $39, up 225% from its June issue price, Saylor’s 64% stake in the company is worth $880 million.

Molding MicroStrategy around his vision of what a company should be, Saylor is contemptuous of what he sees as the “antarctic affectation” of the Silicon Valley culture: “Everybody [there] is busy basically screwing everybody else. There’s no honor among thieves. It consists of a bunch of venture capitalists who don’t have a long-term commitment to their investments, employees who don’t have a long-term commitment to their company and companies that don’t have a long-term commitment to their customers.”

MicroStrategy, run out of a striking 17-story Philip Johnson building in the Virginia suburbs of Washington D.C., is definitely not a bring-your-dog-to-work kind of place. New hires — even seasoned executives — must complete a six-week “boot camp” and pass tests on the company’s software and marketing message. At an annual one-week “university” all employees must attend classes from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., with mandatory study hall from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m. Once a year Saylor takes all employees on an ocean cruise — no spouses invited. “Our culture is part intellectual, part military, part fraternity, part religion,” says Saylor.

Saylor is in the information sorting and extraction business. Retailers, banks and other companies have been spending big bucks to build data warehouses containing masses of information about individual customers and transactions. Then 50 or 100 folks sit at headquarters and use a query engine and tools — sold by MicroStrategy or its competitors — to try to extract insights from these huge databases.

Retailer Best Buy analyzed what products customers buy together — CD buyers tend to load up on film, for example — to help redesign its store layout. PetsMart uses its warehouse to tailor inventory selection for individual markets; dog sweaters are now stocked in larger sizes in rural areas.

In 1996 MicroStrategy brought out its first product allowing users, via the Web or an intranet, to query a database without special desktop software. British retailer Marks & Spencer is using MicroStrategy’s Web software to increase to 800 from 50 the number of employees given access to its 600-gigabyte data warehouse.

Now MicroStrategy has just rolled out “DSS Broadcaster” — a “push technology” product. Preset queries are run against the data warehouse. Users can either receive all reports or an alert — by E-mail or fax or pager — only when there’s an unexpected result. For instance, Spain’s La Caixa savings bank may use Broadcaster to reach all 4,000 branches with alarms about nonperforming loans or with prospect lists for some new marketing push.

Sabre Group, which books $66 billion of travel reservations a year, is also a MicroStrategy customer. It has just built a 2-terabyte (2,000-giga-byte) warehouse of airline bookings that will grow to 4 terabytes when hotel and rental-car bookings are added. About 1,000 Sabre employees will eventually have access to at least some of the data, as will the airlines that now buy tapes of Sabre’s raw booking data, says warehouse manager Kathleen Wayton. Moreover, within the next few years, using Broadcaster, Sabre plans to sell E-mailed reports to both travel agents and companies that want a better fix on their travel costs. A company could also buy Web access to extract such information as which departments book an inordinate number of expensive, last-minute fares.

Saylor also sees a consumer market for warehouse data. One example: An individual bank customer could sign up to receive an alert if his balance got too low. And Saylor predicts that warehoused information about each consumer’s buying habits, combined with push technology like Broadcaster, will dramatically expand direct selling.

“We’re going to use our technology to obliterate entire supply chains, to move the way people shop,” he says. Whether consumers want to be beeped and bombarded with alerts and pitches remains to be seen.

“We’re playing for all the marbles, to essentially win the entire industry, worldwide, forever,” says Saylor grandly. Wait a minute. Aren’t bigger companies — including Oracle and Microsoft — after the same marbles? Yes, but for now MicroStrategy’s tools (which can run on an Oracle database) allow more detailed analysis of big databases.

Other small companies in this market, eyeing the competition, have been merging or selling out. Saylor is contemptuous of that. More of his Silicon Valley thing: “It’s get rich quick. Don’t think about tomorrow. Go fast. Die young.”

Saylor didn’t sell any stock in MicroStrategy’s initial offering. But he and other insiders took a one-time $10 million dividend before the offering. Moreover, public shareholders get only one vote per share, compared with ten per share for insiders. Go for all the marbles — but count your votes.

The son of an Air Force noncommissioned officer, Saylor grew up devouring history books and is obsessed with larger-than-life heroes and zealots. In a long interview he invokes Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Churchill, Caesar and Lincoln. When he enrolled at MIT on an ROTC scholarship, he was surrounded by other high school valedictorians just as bright as he. He concluded there that the “core differentiator” is, “How bad do you really want it?”

Saylor carries this competitive intensity into all areas of his life. Here is his description of a rare seven-day vacation in London: “I saw 5 musicals, one Royal Philharmonic, one Shakespeare, 15 museums and 7 castles.”

Saylor planned to be an Air Force fighter pilot and astronaut. But just before graduating from MIT, he says, a military physical showed that he had a heart murmur, disqualifying him.

So he ended up in New York, working for a struggling computer consulting firm, writing computer simulation models for DuPont. When his bosses demanded he sign an agreement not to compete, he did the opposite. He called DuPont and offered his services as an employee.

At 24, he announced to DuPont that he’d rather be an independent consultant. DuPont gave him office space and a $250,000 contract. Equally important, Saylor talked MIT fraternity brother Sanju K. Bansal, an Indian-born engineer with a master’s in computer science, into leaving Booz, Allen to joint him in the new business.

Bansal, 32, is chief operating officer and has a 14% stake in MicroStrategy, worth $195 million. The soft-spoken Bansal smooths ruffled feathers when the zealot Saylor goes too far. Still, Saylor’s aggressive style sets the tone. At trade shows in 1993, MicroStrategy cranked up its sound system so loud that better-known exhibitors, with more salesmen, couldn’t make their pitches.

Saylor makes no apologies for his grandiose ambitions. “There’s nothing more frustrating than seeing cynics sit there and say, ‘Well, nobody can make any more money because Microsoft and Intel own everything,'” he fumes. “Is the software industry mature, or is it embryonic? I would say it’s embryonic. There will be 100 more Microsofts, not just one.”

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here